And you may find yourself...

...living in a democracy that no longer believes in itself

…wondering if anyone still believes in the rules

Here’s the question that’s been haunting me this year: Is there still a critical mass of us with the will to preserve what remains?

I mean this as a general civic question, not a partisan one. Are there still enough of us who believe that a rule- and law-based civil society is not only desirable and effective, but moral and worth preserving? Or have we reached the perhaps inevitable moment when the will to power wins out?

For most of my forty-four years, I had a naive faith1 that there would always be enough of us—barring some catastrophe—to hold the line. To hold the mini-revolutions that occur each year when we go to the polls and vote out (or in) the bastards who hold those seats until the next election.

I am no longer convinced. Well, how did we get here?

…wondering if this is how the real world ends

It has always been possible to foresee the collapse of democratic culture. What’s harder is to recognize the moment when the collapse stops being a warning and becomes the condition in which we live.

In 1967, Guy Debord wrote that modern life was no longer organized around shared experience, but around representations of experience. The spectacle, he said, was not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images. It is not that politics became theatrical; it is that reality itself was displaced by performance. Citizens no longer acted. They watched. They voted, occasionally, but mostly they consumed the appearance of political life while remaining spectators to its operation.

A generation later, the spectacle was no longer enough. As Jonathan Crary has argued, capitalism demands more than passive consumption—it demands constant availability. In a world where rest is inefficiency and sleep is a market failure, attention itself becomes a battleground. What matters is not truth or deliberation, but whether you are still scrolling, still reacting, still feeding the system with the currency of your engagement. Politics becomes another stream in a continuous feed, competing not with other ideologies but with dopamine.

And then, as Baudrillard warned, the real disappears entirely. We no longer simulate debates over real issues—we simulate the idea of debate. Candidates become brands. Outrage becomes a style. Governance becomes theater without reference. The old structures persist—elections, speeches, hearings—but they no longer mediate anything beyond themselves. They are rituals of legitimacy performed for a public that no longer remembers what legitimacy feels like.

This is not dystopia. It is something far more stable: a culture that has adapted perfectly to its own conditions. It does not collapse under the weight of contradiction. It floats, frictionless, in the absence of reality.

…watching a debate that isn’t a debate at all

Enter Jubilee's Surrounded, where Mehdi Hasan sits alone against twenty self-proclaimed far-right conservatives. The performance is viral bait; the substance disturbing. The spectacle pulls the curtain aside and reveals how perfectly we’ve scripted consent.

When Hasan claims "Trump is defying the Constitution," a young man named Connor rushes to take the chair. You kinda have to see it to believe:

Another panelist echoes similar dismissals: “To be honest, I don’t care about the Constitution.” (Around 30:55 of the video above.)

Hasan’s visible shock becomes the point: “The only good thing about this fascist moment we’re in is that you guys are so open about it.”

This moment exemplifies the convergence of our historical currents:

Debord’s spectacle: the debate show as a performance of outrage and tribal momentum, not reasoning.

Crary’s attention economy: participants train for virality, instant click-note moments, not deliberation.

Baudrillard’s simulation: the constitutional norms persist in form but lose their force; even democracy becomes a style.

More telling is that none of these authoritarian assertions are fringe whispers. They are broadcast, rehearsed, applauded. Hasan didn’t stumble across hidden radicals. He sat across from people who have absorbed democratic language but discarded its meaning.

We built the platforms. We gamed the algorithms—this episode of Surrounded has gone massively viral because of the open, unvarnished positions taken and Hasan’s shock at the insanity of the spectacle. And now we gaslight ourselves by calling the spectacle democracy.

…living in a country where the law still speaks, but only sometimes

Spectacle alone cannot explain what follows. For that, we need a different vocabulary—one that accounts not for the collapse of democratic institutions, but for their continued operation under altered logic. What we are witnessing is not the death of democracy, but its bifurcation: the separation of form and function.

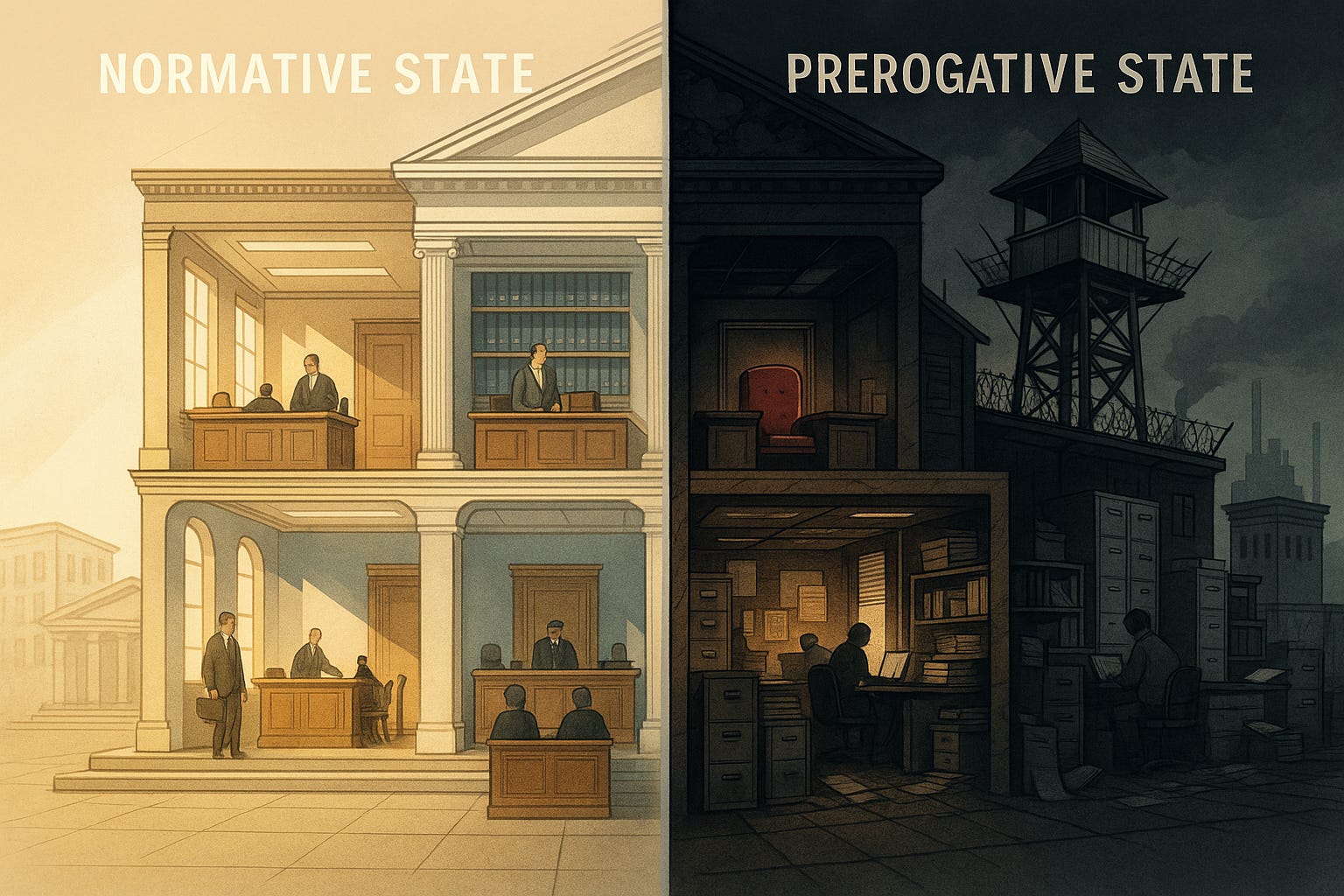

The book I return to now is one I first read in law school: Ernst Fraenkel’s The Dual State. It felt like a warning from an incomprehensible time, then. Fraenkel wrote the book in the late 30s, one of the only Jews still practicing law in Berlin. He had to flee, and smuggled the book out with him. In it, Fraenkel identified what he called the “dual state.” The Third Reich, he observed, did not abolish the rule of law. It split governance into two parallel systems: the “normative state,” where bureaucratic rules and legal procedures continued to operate, and the “prerogative state,” where arbitrary power reigned. The innovation was not the triumph of one over the other: it was their simultaneous coexistence. Law where convenient; will where necessary. For my friends, anything; for my enemies, the law.

Fraenkel was describing a totalitarian mechanism. But the structure he uncovered—the parallelism of legality and exception—has proved surprisingly adaptable. You do not need jackboots to construct a dual state. You need only the willingness to treat constitutionalism as contingent.

Since 2016, the American case has moved unmistakably in this direction. The machinery of governance persists: courts still convene, elections are still held, laws are still passed. But their authority has been rendered conditional. Legal rulings are respected when they affirm desired outcomes. When they do not, they are dismissed as illegitimate—products of corruption, “deep state” sabotage, or electoral fraud. Emil “tell the courts ‘Fuck You’” Bove III, a man who abused his power during his short term in the DOJ in laughably villainous ways, is now a judge on the Third Circuit Court of Appeals.

…unsure why the institutions still work—but not for me

What appears to be a contradiction is, in fact, wholly coherent. The dual state lives: the normative process for routine administration; the prerogative arm for moments of threat, urgency, or loss of power. Executive orders expand. Loyalty supplants expertise. Laws are selectively applied, depending on the political coloration of the target.

The danger is not an abrupt collapse but a steady evacuation of meaning. Democracy remains in appearance: the rituals, the terminology, the institutions. But those forms now operate under a logic that privileges allegiance over law. Courts render decisions, but only those that confirm the preferred narrative are enforced. Elections are held, but only those that validate the ruling coalition are accepted. The rest are noise, obstruction, or treason.

What Fraenkel grasped, and what liberal democracies are reluctant to admit, is that authoritarianism does not always arrive with banners and declarations. It advances by absorption, not replacement. It captures the forms of liberal governance and retools them to serve consolidation. It speaks the language of order, necessity, and national renewal.

…face to face with people who no longer pretend

This is what the young authoritarians on Jubilee revealed. They were not rejecting American democracy. They were articulating its transformation—its mutation into something that preserves institutional shape while inverting its purpose. When Connor said he believed in democracy only until his preferred leader wins, he was not being inconsistent. He was describing the prerogative state. When another participant shrugged off the Constitution—“I don’t care about it”—he was not defying the system. He was expressing confidence that the system no longer matters.

Their ease was the most chilling thing. No disguise, no hesitation, no fear of judgment. They had learned the grammar of democracy, but used it to conjugate power.

This is how republics are lost: not in blackout or with tanks in the street. It will happen in floodlights, our institutions still functioning—just not for us.

…hearing the quiet part out loud

So we return to the question that haunts: Is there still a critical mass of us with the will to preserve what remains?

The answer, I fear, lies not in grand declarations or constitutional conventions, but in smaller moments of choice. In a lawyer’s decision to join a group devoted to dismantling the rule of law, not for principle, but for power. In young Americans casually dismissing constitutional norms as obstacles. In the quiet erosion of professional ethics that once acted as democracy’s immune system.

A friend recently posted about a colleague’s decision to walk away from what she called the law’s true purpose. She quoted Jordan Furlong’s recent piece “What are Lawyers For?”, where he writes that law is “a framework for peaceful co-existence, a structure for regulating power, and a blueprint for moral architecture.” To this, I say: yes. This is, and has always been, the lawyer’s most critical role. That’s why we are always among the first to be attacked by authoritarians. I suspect what bothered my friend, what hit her right in the heart, was that her colleague abandoned this calling for an explicit reason: power. Nothing more, nothing less.

This is what Fraenkel understood: authoritarianism doesn’t need to destroy institutions. It only needs to hollow them out. The forms remain. The language persists. But the animating spirit—the belief that these things serve something larger than power itself—quietly dies.

And perhaps that is the most disturbing revelation of our moment. Not that authoritarianism advances through revolution, but that it advances through adaptation. It does not need to convince everyone—only enough. It does not need to end democracy, only to make it optional. It does not need to eliminate the rule of law, only to make it contingent.

We built the platforms that turned citizens into spectators. We created the conditions where spectacle became indistinguishable from governance. We built a media ecosystem that rewards performance over principle. And now we wonder why so many conclude that performance is all there is.

Are we still interested in civil society? Or has naked power become the order of the day?

There has always been a faction drawn to raw power. For a time, there were enough of us who believed rules and norms were more than window dressing. That belief held the rest at bay.

Isn’t it pretty to think so?

Do enough of us still believe the difference between law and power—between governance and domination, between citizenship and spectatorship—matters enough to fight for?

This faith was "naive" not because it was blind to America's deep and ongoing injustices. The 'prerogative state,' to borrow Fraenkel’s term, has been a brutal feature of American history, from Jim Crow to the abuses of COINTELPRO. Rather, the faith was in a baseline consensus that these were violations of the nation's constitutional ideals, not expressions of them. It was a belief that the 'normative state,' however flawed, provided the framework for its own correction. The unsettling shift addressed here is the movement of the rejection of those constitutional ideals from a fringe position or a covert state action into an open, mainstream, and performative political identity.

Ah you spritely 44-year-olds and your loss of innocence arcs. I listen to a lot of conservative talk radio (because you have to know what is happening in the world) and I overhear a lot of youtube and tiktok nonsense (2 teenage boys). I think you have (1) a lot of scared lonely old people that do not understand the world and need attention and comfort and respond to repetitive and soothing messaging because no one is taking care of them and no one is listening to the pain of the old; (2) some very mission-driven adults who are strategic and know what outcomes they want (and it's a version of patriotism that does pay lip service to the Constitution, lionizes the founding fathers, and hero worships the framers) and are making serious progress on the plan; and (3) some angry teenagers (loosely aged 13-43) who just want to play Fortnite and be left alone and for their teachers and mothers and anyone who reminds them of their teachers and mothers to get off their backs for whom the Constitution is just more school. This last group also finds very appealing the historical stories of when people like them were all-powerful (not realizing that they still are the dominators in all things).

In biology class in college I learned about the concept of entropy. It says that everything in the universe tends towards randomness. The higher the entropy a system has, the less ordered it is and more random.

The second law of thermodynamics states that entropy inside a system can only increase or stay the same; it cannot decrease. To maintain order, the system must give off energy, typically in the form of heat. This heat, however, adds to the entropy of the surrounding environment, thereby increasing the overall entropy of the universe.

I would say this is what we have here — a build-up of entropy inside the system. There are those who feel they have been given the short end of the stick of life. They see others succeeding while they struggle. They see the system as designed to help others, to their detriment. So what do you do when you feel you have been treated unfairly by a system? You shake it up. You add randomness, energy. You set the world on fire and figure the only place you can go is up.

There are many who find themselves in a better place as a result of the shaking. Or at least feel they are on a more equal footing with those who were unfairly benefiting with the system previously. Once there, it is in the person’s best interest to do what is necessary to maintain that position, lest they fall back down again. In this case, that means more shaking. More fire. Supporting entropy.

And once you get control of the system, you can ensure the shaking continues and put measures in place to ensure someone can't stop the shaking.