Here are your links to the Pennhollow playlist so you can listen along: Tidal and Spotify. (And a gentle reminder that Tidal pays artists more per play and the sound quality is better.)

I haven’t been listening to many records this year. This is unusual for me. Hell, my record player is sitting disconnected on my dining room table (the toddler loves nothing more than playing with the lid of the turntable and yanking around the arm and cartridge), but that’s not why I haven’t been spinning vinyl.

Since January, I’ve been listening to a single playlist again and again and again. Every night, for hours on end. Starting at about 8:30 pm and going until 1:00 or 2:00 am. The songs on this playlist have created note-perfect neural grooves in my gray matter. It’s made me think a lot about how soundtracks shape the world around them.

Ask most writers about their writing routine, and you’ll find that every book has its own soundtrack. A mix tape or playlist, an album or artist that played on repeat during the writing of the novel. One of my favorite writers, Michael Chabon (whose Substack you should absolutely check out and subscribe to), said this about his own process:

I always listen to music when I work. I find that I’ll be listening to something for years, then I change project and it doesn’t work anymore. On Telegraph Avenue, I was listening to 1960s and 1970s soul jazz and jazz funk — I call it backbeat jazz. I discovered this music in the process of writing the book. I listened to it and it even became incorporated in the prose in some way.1

There is something about the shape of the music that helps shape the world of the novel, and in the case of a novel like Telegraph Avenue (or, I suspect Mann’s Doctor Faustus, Egan’s A Visit From the Goon Squad, Mitchell’s Utopia Avenue, Zadie Smith’s Swing Time, etc., etc.), I cannot fathom how you would go about writing without being immersed in a very specific sonic playground.2

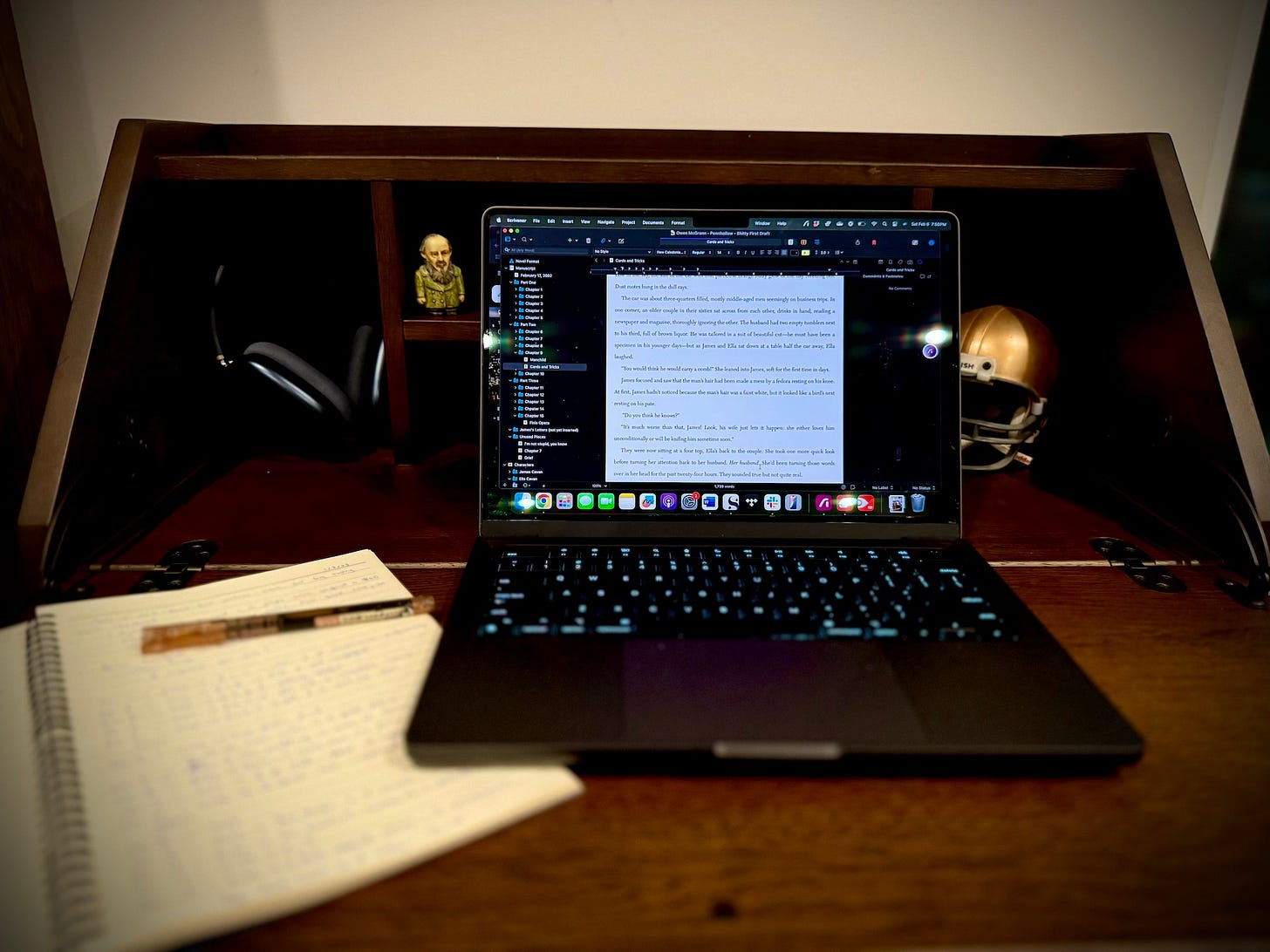

The repeated nightly ritual of putting the little monster to bed, finishing dinner, putting on my headphones, and opening my narrow writing desk creates something of a trance. Some of that may be exhaustion—I’ve likely been up since six. But more than the fatigue, it’s the music of Pennhollow that sets me down in 1940s Pittsburgh. Some days I’m surprised I don’t have soot on my shoulders when I finally stand to go to bed.

One of the few deliberate choices I made when writing Pennhollow was that the music—the swing and bop, the clubs, the postwar tension—and the city of Pittsburgh had to be fully formed characters in their own right. Music and city were always intertwined. Jazz flowed through the Hill; making both central to the novel was less a choice than a necessity.

Making the music and the city central features of the book gives shape, but each presents its own challenges. We’ll talk a bit more about music in a moment, but a quick note about writing Pittsburgh as a character. The city is one of the few in the United States that is immediately and only itself. Columbus is Indianapolis is Des Moines is Omaha. When you are dropped in New York or New Orleans or San Francisco, you know instantly where you are. Pittsburgh is the same way.

And yet, there’s not much of a literary language that sustains Pittsburgh as a place. Chabon has done more than anyone recently to create a literary Pittsburgh with The Mysteries of Pittsburgh and Wonder Boys. Maybe he’s the only writer lately who has broken through using Pittsburgh as place. You have August Wilson, of course. If I wrote that a woman is walking down Bleecker Street or Baker Street, meandering through the Tenderloin or the Left Bank—I bet in your head you’re thinking, “New York, London, San Francisco, Paris.”

But if I write Wylie Avenue, the Strip District, or Walnut Street? You’re probably coming up blank.

It’s not much of an exaggeration to say that Billie Holiday is the muse I invoked each night as I sat down to write. The first song on the playlist is “Lover Man,”3 which one of the characters whispers into the ear of another character in the opening chapter as they dance at the Musician’s Club.

Lady Day is, to my mind, the sine qua non of jazz singers. In a novel overflowing with music (the first twenty-three songs on the playlist appear in the novel, in that order), this is the song that we first encounter. She captures more in a slight break in her voice than the most “perfect” singers in the game. There is something deeply human about Billie, something just devastating, and that is the mood I wanted to set for the book. “Lover Man” was the first song I wanted readers to hear when moving through Pennhollow. I think the first chapter of any book is something of a contract with the reader. By the end of the chapter, the reader should know what to expect from the novel; I don’t mean that the reader should understand the plot or every one of the characters, but there probably shouldn’t be something that is formally shocking later. The tone and the mood should be established. Billie tells you all you need to know about what’s coming.

1946 was a threshold year, a time of change—and with change comes conflict. One way I wanted to explore these social fissures was through the evolution of jazz from swing to bebop. We now think of all of this simply as “jazz,” but time collapses difference; it’s hard now to hear much between Bach and Mozart.

Swing was prewar music: dance music played with full bands (or “orchestras”). Some of the most memorable jazz standards—“Sing Sing Sing” and “In the Mood”—come from this period. This is good music, often great music. We still use some of the innovations in contemporary music. (Modern drumming leads right back to Gene Krupa.) Still, it’s pop music.

Bebop was something else entirely. Gone were the big bands; in their place were tight four-, five-, or six-piece bands. Everything was stripped down, elemental, peripatetic. Esoteric. Bop introduces names you surely know: Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie. It was this music that distinguished jazz as not merely dance music but serious music.

This tonal shift mirrored the social one. The older generation was left at a loss by bop and the boys returning from the front found themselves changed. As Pittsburgh exited the war, it was the industrial capital of the world. For decades during the Cold War, the city was third in line for a Soviet nuclear strike, after only DC and NYC. Japanese steel was not yet a thing. The city was about to unleash its first Renaissance.4

And yet, for all of what Pittsburgh, and the United States more generally, had going for it, this was a time of fracture and repair. An anxious time of return and a new world not yet quite born.

There’s no better music for such a moment than bebop. And after Harlem, there was no better scene than the one in Pittsburgh. It’s the soundtrack of a city—and a century—learning to live with the noise of its own becoming.

https://medium.com/@smilodon207/what-music-do-celebrated-authors-listen-to-while-they-write-39f04ddf7f28

A quick note to say: I have to think all those songs in Pynchon’s books are actual songs that the man sat down and wrote. They probably have chords and distinct melodies. I sure hope there are either recordings or sheet music somewhere!

Hey Melanie Jackson! Can you imagine the new audiobook versions?! Make it happen!

For as transcendent as Billie was, I have a hard time saying her version of “Lover Man” is the best. Perhaps “best” is the wrong way to think of it. Charlie Parker has a version of the song where he plays the lead, clearly drunk and strung out. Where Billie’s version is melancholy with a hint of hope, Bird’s version is one of the saddest tracks I’ve ever heard. Check it out:

Incidentally, the first Renaissance destroyed the lower Hill, a predominantly black neighborhood, which was home to all of the clubs where Pennhollow takes place.

I don’t have a soundtrack for my book, although equally, this first one is not a work of fiction, so perhaps that is why.

I do sing though, copiously and two choirs-off-book-by-memory-at-the-Opera-House copiously.

Also, sleep; being chronically underslept is badder than Michael Jackson. Our bodies keep the score. I saw the top sleep professor in the world in conversation at the Sydney Writer’s Festival and it’s scary how bad not enough sleep is for our health. So, that’s my other takeaway on a 6am wake up to a 1-2am end point. Matt Walker ‘Why We Sleep’, if you’re interested is a densely scientific (and fascinating) wake-up call