One significant advantage of coming to writing a novel and trying to push it to publication a bit later in life is I’ve already experienced success and failure in creative spaces. There’s nothing quite like bringing a new, unfinished song into practice only to have your bandmates shake their heads: nope, not even worth jamming on. Nothing so brutal as a senior partner take a red pen to a critical brief to be submitted to an appeals court. There is no space for ego. Only the result matters.

Seth Godin, among others, frequently says the only way to get to good ideas is to have a lot of ideas. The only way to good work is to not be precious about your work. This is something that has been beat into me over the past twenty-five years of creating music and art and businesses. It’s okay if it’s not good; the real question is whether there’s a path toward making it good.

I finished the surface-level edit of my novel Pennhollow at the end of May and, before I could change my mind, sent the file off to the developmental editor I’d hired to help me bang the thing into shape. I knew that I had good pieces in the book, but well-written sentences are a necessary but not sufficient condition for a good book. I won’t lie. I’m trying to write a great novel. Maybe that’s arrogant. So be it. I knew from experience that if I waited until the next day to send the book to Jordan, my editor, my resolve may have been lost.

Creative journeys are confidence games: you have to choose the next, impossible step, again and again.

After I sent the manuscript off to Jordan1, the waiting game began. Objectively, I knew it would take the full month to work through a nearly 100,000 word novel. I was quite aware that Pennhollow is in some senses, a difficult book: nonlinear, subtext being more important than text, some stream of consciousness thrown in for good measure. It’s not the kind of book an editor can consume and turn around useful edits on in a week. Yet the five-week wait felt like an eternity, the sword of Damocles hanging over my head ready to fall and announce whether there was a salvageable book.

You see, one of the odd experiences when writing a novel is that you know there are issues that need attention. I was well aware that the underlying relationship between two of the main characters was insufficient to carry the Greek tragedy stakes that appear at the end. I knew that the letters James sent home during the war, and which appear between chapters, were necessary but not dynamic enough. I knew that the criminal underbelly of one of the plotlines was probably too understated for it to hit the way it needs to.

You can know these things, but not see a way through. When you live with a book, when you dine with the characters and listen to jazz with them every night, they become more difficult to see, not easier. You meld into the damn thing in a way that makes it very hard to see the thing and see paths through the problems.

All of this was suffocating me as I awaited Jordan’s edit, consumed with the fear—at times, the certainty—that his response would be that of my bandmates shaking their head and declining the invitation to jam out the new tune.

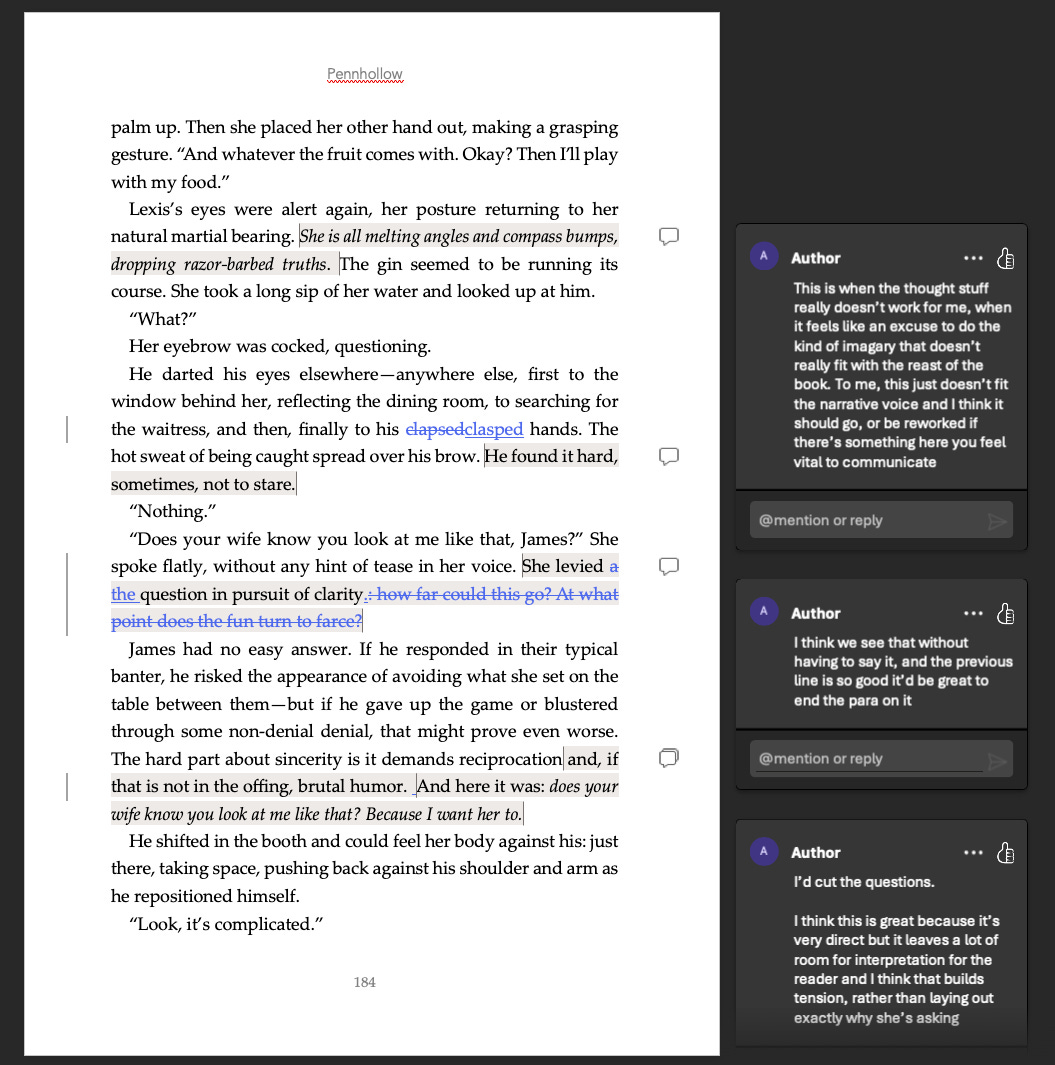

I received the edit of a 350-page book at 5:50 pm, and I anxiously opened the file. Jordan said some nice things in his note to me, but I know that sometimes those notes are attempts to soften the blow. The Word file took forever to load. As the document populated, I scanned through the document and my heart sank. Comments everywhere. Multiple on every page, sometimes as many as ten or fifteen.

In the days leading up to receiving Jordan’s edit, my friend Allison—herself a published author and talented writer—told me to expect the five stages of grief upon receipt. Man, was she right. She also said: after the initial rush of emotions dies down, you’ll realize that the editor is usually right. Her insight helped me frame how I took in Jordan’s legion of comments, put me in the right mindset from the outset. But I don’t think I would have been able to take the landslide of edits and critique (and praise!) if I hadn’t lived through twenty-five years of creative life first.

What caught me off guard wasn’t the grief. I’d been bracing for that. It was how quickly the grief gave way to momentum.

Not instantly. The first time through, I skimmed. I read through the entire 350-page manuscript and the notes that first night. I caught the volume of it—margin notes everywhere, whole paragraphs or sections marked for collapse or deletion—but I couldn’t hold any single thought. It was like walking into a room where every person is talking at once and trying to make eye contact with you. I closed the file.

The next day, I opened it again.

This time I didn’t just see comments—I saw movement. The things I’d felt were wrong but couldn’t fix started to loosen. I found comments from someone deeply engaged with the work, excited about its promise. Comments from somebody fighting to get the book to meet its promise.

The relationship between James and Ella, which I knew wasn’t carrying the weight it needed? He put his finger on the problem right away: we don’t believe they ever liked each other. Without that, nothing else lands. He didn’t say “write new scenes” (even though I’m presently in the middle of a wholesale rewrite of Chapter 2). He told me why the existing ones didn’t work, and how they could. He showed me how to build a foundation that would let the unraveling mean something.

The wartime letters? I thought they were doing a lot of work. Turns out they were doing the same work, over and over. Jordan broke down exactly how they flatten out: same emotional pitch, same rhythm, same tropes. And he offered ways to let them stretch—tone, structure, even which letters shouldn’t appear.

And then there was the criminal subplot. I knew it wasn’t landing, but I didn’t know why. Jordan did. He explained how and when a reader wants to almost guess the reveal—how good tension works like a tightrope just long enough to wobble on. The notes weren’t vague. He told me where to plant the signs, where to lean in, where to let the thread go slack. That was the moment the book stopped feeling like a deadweight and started to feel like something I could shape again.

By the end of his report, I wasn’t staring at a wall of problems. I had a map. Not a clean one. Not a shortcut. But a real one. I could see the contours of the thing again.

Which is why that early training—getting over the preciousness—matters so much. If I’d been clinging to the version I already had, I wouldn’t have seen what Jordan was showing me. And what he was showing me wasn’t just critique. It was a way back inside the book, past the fog, to where the work actually lives.

It’s funny: when I told some folks I’d hired an editor, their reaction was that I was farming out the work of the book. In reality, Jordan pushed me back into the work, now with ambition rekindled and the insight of some distance. My head’s back in the game. The work starts now.

If you are ever in need of a superlative editor, please reach out and I will put you in touch with Jordan.

Hey! Pretty sure I said your characters have always hated each other. ;)

Eh, there were more redlines in the last contract I reviewed. 😆

But I am glad to see that things are progressing and that you see the feedback for what it is, and not as judgment of your ability as a writer.